By Fall 2017 M-VETS Student-Advisor

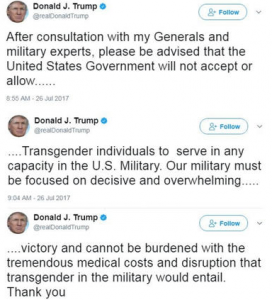

In what was one of his most controversial actions as president thus far, on July 26, 2017 President Donald Trump issued a series of tweets addressing transgender policy in the U.S. Military.[1] The tweets stated, “[a]fter consultation with my Generals and military experts, please be advised that the United States Government will not accept or allow…Transgender individuals to serve in any capacity in the U.S. Military. Our military must be focused on decisive and overwhelming…victory and cannot be burdened with the tremendous medical costs and disruption that transgender in the military would entail. Thank you.”[2] An official memorandum followed on August 25, 2017, which helped explain the timeline of the policy implementation, indicating that the new policy would begin to take effect on January 1, 2018.[3] In many ways, this potential policy-change from President Trump is in keeping with the trend of constantly evolving military policy on this important issue over the last decade and discussion surrounding the constitutionality of such a change has been swirling.

In 2011, President Obama repealed “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” allowing lesbian, gay, and bisexual service members to speak honestly about their sexual orientation without fearing repercussions for their military careers.[4] The repeal did not, however, change policy regarding the right of transgender individuals to serve in the military.[5] In fact, the Department of Defense guidelines at that time “described transgender people as sexual deviants.”[6] Years later though, the end of Obama’s administration brought significant changes for the rights of transgender individuals, wanting to or already, currently serving in the military.[7] In 2016, Defense Secretary Ashton B. Carter announced new Department of Defense policies that both permitted transgender individuals to serve openly, without fear of discharge or separation, and detailed the process “by which a serving transgender Service member may transition gender,” during his or her time in service.[8] Additionally, the policy stated that, beginning in July 2017 for the first time in history, “the military Services will begin accessing transgender applicants who meet all standards—holding them to the same physical and mental fitness standards as everyone else who wants to join the military.”[9] This change in particular, was extremely significant, since an individual that had undergone sex reassignment surgery and/or hormone therapy had never previously been considered for acceptance into the military.[10] These changes were largely based on a research study commissioned by Mr. Carter, a few months earlier, which indicated that, were the military to fund medical transition surgeries, rates of substance abuse and suicide would decrease.[11] Funding of transitional procedures would cost somewhere from $2.4 to $4 million annually, totaling 0.13% of spending on military healthcare.[12]

Since President Trump’s announcement on the issue this summer, debate surrounding the issue has sparked a seemingly endless onslaught of constitutional, strategic, and moral questions. Those opposed to President Trump’s new policy argue that it violates the Due Process clause,[13] marginalizes the transgender community, and is unsupported by any defensible rationale.[14] These arguments were upheld in the recent decision in the D.C. District Court, in which Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly issued a preliminary injunction blocking aspects of President Trump’s new policy.[15] The basis for the injunction simply stated that the policy “does not appear to be supported by any facts.”[16] It did not address whether or not the military should be responsible for the costs of sex-reassignment surgery, but blocked the aspects the policy concerning enlistment and retention of transgender military members.[17] In response to the injunction, Carl Tobias, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law, predicted that “the Trump administration [will] likely have to go all the way to the Supreme Court to have any chance of getting the preliminary injunction nullified.”[18]

This prediction is insightful, particularly since the transgender issue implicates many apparently conflicting constitutional protections.[19] Courts have traditionally held that many constitutional protections simply do not apply to the military in the same way they apply to the general public, and the analysis for determining whether a military policy is constitutional is necessarily different than for another publically or privately funded policy.[20] For example, in Katcoff v. Marsh, the court refused to analyze the question of whether the military chaplaincy was constitutional “in a sterile vacuum.”[21] Rather, the court made clear that because both the Establishment Clause and the chaplaincy must be considered within a historical context from a purposive framework, the current test that was most often used to determine whether an Establishment clause violation exists was not appropriate.[22] Additionally, the court reiterated Congress’ War Power, stating that when a matter provided for by Congress in the exercise of its war power and implemented by the Army appears reasonably relevant and necessary to furtherance of our national defense it should be treated as presumptively valid and any doubt as to its constitutionality should be resolved as a matter of judicial comity in favor of deference to the military’s exercise of its discretion.[23] Therefore, when Congress implements a policy “necessary to furtherance of our national defense,” a constitutional inquiry must begin with a presumption in favor of the military, due to the “constitutional power of Congress to raise and support armies and to make all laws necessary and proper to that end” which is “broad and sweeping.”[24] This deference is often referred to as the “doctrine of nonreviewability,” but it does not function as strongly in issues involving due process as it does in other areas of military policy creation.[25] Ultimately, therefore an analysis of the constitutional legitimacy of denying transgender individuals an opportunity to serve in the military must take into account the context of the Due Process clause and the presumption in favor of the military, in keeping with the extensive war powers permitted. [26]

While the Supreme Court has not yet ruled on the issue of whether sexual identity is a protected class under Title VII or the Due Process Clause, several circuit courts and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission have affirmatively held that discrimination against a person based on transgender status constitutes discrimination “because of sex” under Title VII.[27] If the Supreme Court affirms this ruling in the future, and translates it to Due Process precedent, then President Trump’s policy would likely be reviewed according to intermediate scrutiny standard,[28] requiring the government to prove that the differential treatment “furthers an important government interest in a way that is substantially related to that interest.”[29] And yet, Congress and military leaders are permitted to deny equal protection in the name of “military necessity” all the time, due to the expansive war powers, which would make such a Supreme Court case extremely interesting.[30] For example, the military disqualifies individuals from service for an extensive list of medical reasons, including gluten allergies.[31] Of course it’s impossible to draw a direct comparison between transgender individuals and those with gluten allergies, but the comparison highlights the military’s ability to discriminate in ways that other employers would never be permitted to, for the sake of good order and discipline.

I have witnessed firsthand the tensions that exist between a military commander’s need to enforce physical appearance standards for certain individuals, according to gender, and the individual’s mental health needs to stray from those standards prior to be fully transitioned to the gender that he or she identifies with, since oftentimes in military regulations an individual has to reach a certain point in hormonal therapy before they are officially considered a different gender. Ultimately, all these tensions point to what may be a major Supreme Court case in the near future, in which the Court will hopefully wrestle with these tensions between the Due Process clause and the war powers.[32]

[1] Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump), Twitter (July 26, 2017, 8:55 a.m., 9:04 a.m., 9:08 a.m.), https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump.

[2] Id.

[3] Military Service by Transgender Individuals, Presidential Memorandum for the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of Homeland Security (Aug. 25, 2017), https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/08/25/presidential-memorandum-secretary-defense-and-secretary-homeland.

[4] Kayla Quam, Unfinished Business of Repealing “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell:” The Military’s Unconstitutional Ban on Transgender Individuals, 2015 Utah L. Rev. 721, 721 (2015).

[5] Id.; see also Jonah E. Bromwich, How U.S. Military Policy on Transgender Personnel Changed Under Obama, N.Y. Times (July 26, 2017), https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/26/us/politics/trans-military-trump-timeline.html.

[6] Jonah E. Bronwich, supra note 5.

[7] Transgender Service Member Policy Implementation Fact Sheet, U.S. Department of Defense, https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/2016/0616_policy/Transgender-Implementation-Fact-Sheet.pdf (last visited Nov. 4, 2017); see also Jonah E. Bronwich, supra note 5.

[8] Id.

[9] Transgender Service Member Policy Implementation Fact Sheet, supra note 7.

[10] This policy was mandated by DoDI 6130.03, which states that a “[h]istory of major abnormalities or defects of the genitalia[,] including but not limited to change of sex” disqualifies a person from entering the military. Department of Defense Instruction No. 6130.03 (Sept. 13, 2011), available at https://community.apan.org/wg/saf-llm/m/documents/184254.

[11] Jonah E. Bronwich, supra note 5.

[12] Sabrina Siqqiqui, Transgender Troops Can Stay in the Military for Now, James Mattis Says, the guardian (Aug. 29, 2017), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/aug/29/transgender-troops-can-stay-now-james-mattis-trump-ban.

[13] Kayla Quam, supra note 4; see also U.S. Const. amend. V.; Ariane de Vogue, Judge Blocks Enforcement of Trump’s Transgender Military Ban, CNN Supreme Court Reporter (Oct. 30, 2017), http://www.cnn.com/2017/10/30/politics/judge-blocks-trump-transgender-military-ban/index.html.

[14] Brief for Massachusetts, et al. as Amici Curiae Supporting Plaintiffs, Jane Doe v. Donald J. Trump, (2017) (No. 17-cv-1597), available at https://ag.ny.gov/sites/default/files/doe_v_trump_-_state_amicus_brief.pdf.

[15] Justin Jouvenal, Federal Judge in D.C. Blocks Part of Trump’s Transgender Military Ban, The Washington Post (Oct. 30, 2017); see also Ariane de Vogue, supra note 13.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Namely Due Process protections in conflict with Congress’ War Powers.

[20] U.S. Const. amend. V., see also Katcoff v. Marsh, 755 F.2d 223, 236 (2nd Cir., 2008)(holding that the Chaplaincy did not violate the Establishment Clause, because it promotes free exercise of religion and is within Congress’ War Powers).

[21] Katcoff v. Marsh, supra note 18 at 232-33.

[22] Id.

[23] Id. at 234 (citing Rostker v. Goldberg, 453 U.S. 57, 64-68 (1981).

[24] Id.; United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 377 (1968).

[25] Heather S. Ingrum Gipson, “The Fight for the Right to Fight”: Equal Protection & the United States Military, 74 U.M.K.C. L. Rev. 383, 385 (2005-2006).

[26] This is similar to the analysis of the chaplaincy in Katcoff v. Marsh. Katcoff v. Marsh, supra note 18. Of course, however, this would more likely be true if Congress backs President Trump’s policy, since Congress holds greater war powers than the Executive.

[27] 42 U.S.C.A. § 200e-2(a); Roberts v. Clark County School District, 215 F.Supp. 3d 1001, 1014 (D. Nev. 2016).

[28] This was the standard the Eleventh Circuit used in the analysis for Glenn v. Brumby. Glenn v. Brumby, 724 F.Supp.2d 1284,1997 (N.D.Ga. 2010).

[29] David S. Kemp, Sex Discrimination Claims Under Title VII and the Equal Protection Clause: The Eleventh Circuit Bridges the Gap, Verdict: Legal Analysis and Commentary from Justia (Mar. 19, 2012), https://verdict.justia.com/2012/03/19/sex-discrimination-claims-under-title-vii-and-the-equal-protection-clause.

[30] Heather S. Ingrum Gipson, supra note 23.

[31] Rod Powers, Military Medical Standards for Enlistment & Commission, US Military Careers (Sept. 8, 2016), https://www.thebalance.com/military-medical-standards-for-enlistment-and-commission-3353967; Patricia Kime, Medical Mix-Up Sidelines Army Sergeant’s Career, Military Times (Jan. 14, 2016), https://www.militarytimes.com/2016/01/14/medical-mix-up-sidelines-army-sergeant-s-career/.

[32] As mentioned previously, however, such a case would only likely be viable if Congress and his senior military advisors back President Trump’s policy, since Congress holds more war powers than the Executive.